Be Careful What You Wish For: A little piece of Soviet style totalitarianism in our own backyard

My article “The art world’s ‘hidden enemy'” on the subject of purges for sexual misconduct in the art world is out in the Decemer issue of The New Criterion. (The New Criterion, Volume 36 Number 4, on page 86).

Here is the full text of my article:

The art world’s “hidden enemy”

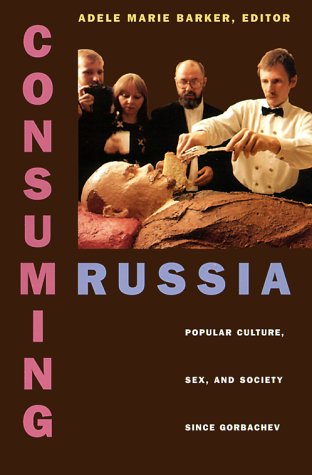

While preparing my latest lecture on Russian art of the 1920s and ’30s, I was struck by some disturbing parallels between the current American and the historical Soviet cultures of “unmasking the hidden enemy.” The comparison was brought on by a group letter, written in the style of an early-twentieth-century Russian Modernist manifesto and headed: “We’ll stay silent no more over sexual harassment in the art world.” Published in The Guardian on October 29 with over one hundred signatures, the letter called upon all women in the arts (it actually referred to them as “workers of the art world”) to denounce their abusers, citing “an urgent need to share our accounts of widespread sexism, unequal and inappropriate treatment, harassment, and sexual misconduct, which we experience regularly, broadly, and acutely.” These women identified as a victimized group, claiming to have been “groped, undermined, harassed, infantilized, scorned, threatened, and intimidated by those in positions of power who control access to resources and opportunities.” In other words, the letter was an open call for hashtags, a free-for-all social media dispensation to accuse any male colleague who, at some point in our careers, subjected any of us to sexual harassment. Crucially, the definition of “harassment” is left vague, since it encompasses everything from forcible rape to “gender microagression,” which was recently identified as a “gateway to sexual harassment and sexual assault.” Anyone paying attention to the events of the past few months would recognize this letter as one among many such appeals for narratives of abuse. Just the other week I received an online document named “shitty_media_men,” circulated with an injunction: “never share this document with a man.”

Why now? Following revelations of Harvey Weinstein’s atrocious behavior, the entertainment industry is taking a close look at its unflattering reflection. But as Weinstein’s longtime collaborator, the screenwriter Scott Rosenberg, revealed in his widely publicized Facebook post: “Everybody- fucking-knew.” It hardly came as a surprise that, in an industry so heavily dependent on physical appearance and sex appeal, young, vulnerable women would be victimized by powerful and unscrupulous men. The art world, which has long been moving in the direction of the entertainment industry (Björk’s dire solo show at moma is just one sad example), followed up with its own soul- searching. And voilà, the first name came up in all its eccentrically bespoke-color-suited glory: Artforum co-publisher Knight Landesman. He was named in an Artnet News article listing complaints of “inappropriate behavior.” The story was further explored by Artsy, Artnet again, The Guardian, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. Landesman resigned from the magazine, as did its executive editor, Michelle Kuo. Artforum issued a statement of apology, but several gallerists who deemed the apology insufficiently sincere have threatened to boycott the magazine by pulling their advertisements.

It remains to be seen whether the other three Artforum co-publishers will be able to prove their ideological purity and retain their advertising bases. Lisa Spellman, the owner of 303 Gallery who threatened to boycott Artforum, says she “will watch how the publishers handle” the lawsuit caused by the Landesman debacle. Undoubtedly the promotion of the long-serving, universally liked magazine employee David Velasco to the position of editor-in-chief will burnish the publication’s image. Velasco has already clarified his position: “The art world is misogynist. Art history is misogynist. Also, racist, classist, transphobic, ableist, homophobic. I will not accept this. I know my colleagues here agree. Intersectional feminism is an ethics near and dear to so many on our staff. Our writers too. This is where we stand. There’s so much to be done. Now, we get back to work.” It will be particularly interesting to see how Artforum plans to square the classist circle while maintaining its sleek Vogue-of-the-art-world image. In my experience, its gamine, ingénue employees often come from seriously privileged places. The external label stitching on their luxury Maison Margiela clothing is hard to miss.

As the subtitle of the manifesto states, its signatories “held [their] tongues, threatened by the power wielded over [them] and promises of institutional access and career advancement.” Forgive my cynicism, but I cannot help but think that the key to the timing of the letter is that the “workers of the art world” who signed it, having already achieved the desired “institutional access and career advancement,” and emboldened by the long-overdue disclosures around rape and sexual violence in the entertainment industry, decided to take this opportunity finally to cleanse the environment of what they perceive as undesirable elements. In the process, they risk going into a purging mode strikingly reminiscent of what happened under Comrade Stalin in my native country, the former USSR.

It seems to me that despite the bombastic phrasing that recalls the furious tone of Russian avant-garde manifestos, these women do not realize where the primrose path of purging is likely to lead. If Soviet history is any indication, we should be seriously concerned by such ignorance. Once the processes are initiated, the enemy is identified, and the cogs of the apparatus are set in motion, there will be little reason to stop the purging at alleged sexual harassers. The clean-up will continue until the ranks of the art world are rid of any and all offensive elements. It is by no means impossible that even the righteous signatories of this letter may one day find themselves denounced for racism, classism, transphobia, ableism, homophobia, or any of the proliferating multitude of microagressive offenses.

Revolutions are famous for devouring their children. In the Soviet purges, terror came in ubsequent waves, each engulfing additional enemies and cleansing the system until the cleansers themselves were cleansed. Wendy Goldman’s Inventing the Enemy: Denunciation and Terror in Stalin’s Russia describes the nightmare:

Communist Party leaders strongly encouraged ordinary citizens and party members to “unmask the hidden enemy” and people responded by flooding the secret police and local authorities with accusations. By 1937, every workplace was convulsed by hyper-vigilance, intense suspicion, and the hunt for hidden enemies. Spouses, co-workers, friends, and relatives disavowed and denounced each other. People confronted hideous dilemmas. Forced to lie to protect loved ones, they struggled to reconcile political imperatives and personal loyalties. Workplaces were turned into snake pits. The strategies that people used to protect themselves—naming names, pre-emptive denunciations, and shifting blame—all helped to spread the terror.

I know this story all too well. My paternal grandfather, Semyon Friedman, was a trained lawyer and a card-carrying member of the Soviet Communist Party, which he joined in 1928. He began working with Sergei Kirov, who became the head of the Communist Party in Leningrad. By the early 1930s my grandfather was appointed an executive head of the regional party cell, where he worked for just over a year until Kirov was assassinated, which prompted a wave of purges against dissident elements of the Party. Robert Conquest, as readers of this journal well know, would dub this period in Soviet history the “Great Terror.” The pattern was always the same: people were accused of various crimes, arrested, brutally interrogated, forced to confess, convicted, deprived of their rights, and finally either handed a lengthy prison sentence in a hard-labor camp or shot in a cell and buried in an unmarked grave.

When my grandfather was arrested in the fall of 1937, his wife, my grandmother, was due to give birth to their second son—my father. They were prepared for the worst, for people were always convicted, and since they expected my grandmother to be arrested as well (immediate family members over the age of twelve were sent to the camps; children under that age were placed in the care of the State and brainwashed), they made arrangements to hand over their newborn son to close friends for adoption. Miraculously, following the nkvd head Nikolai Yezhov’s fall from power, the three members of the special troika—a committee that was to conduct a speedy investigation into my grandfather’s alleged crimes—were themselves purged and executed. My grandfather was released with full reinstatement of his rights. He promptly retrained as a doctor, stepping back from the meat- grinder of Party politics. Amazingly, he remained a life-long believer in Communist ideals, continuing to lecture on politics and ideology at workers’ clubs. He never discussed the charges leveled against him: as far as he was concerned, justice had prevailed. That’s because he was an ideologically pure Communist, and for people like him, ideological purity was über alles.

There lies the similarity between the Stalinist purges and the increasingly paranoid milieux of day’s artistic, cultural, and academic scenes. Just as the 1919 injunction by an early Soviet art organization of Communists- Futurists (Komfut) “to wage merciless war against all the false ideologies of the bourgeois past,” led to the purges of the 1930s, so the clarion call to share narratives of sexual misconduct, if unchecked, is likely to lead to more careerist purging and power reshuffling— during times when “art workers” might do better to unite in the face of much larger and more ominous political and cultural challenges. We are already witnessing the privately circulating lists of alleged and rumored offenders, the manifesto tone of group-signed letters, the “us vs. them” mentality, the self-denunciation and apologies. The accused are immediately ostracized, their careers ruined, often well before any corroborating evidence comes to light. Benjamin Genocchio’s recent discharge from his duties as the executive director of the Armory Show is a case in point.

Of course perpetrators of sexual violence ought to be prosecuted and punished. My issue is with the open call to indictment for an incongruously broad range of sexual “offenses”; such a call abrogates the principle of presumption of innocence. I understand that the goal is to enable victims to speak up, and I am aware that victims of sexual violence are vulnerable to blame. But what if the choice is between being safe and being free? The self-identified “workers of the art world” must realize that once they initiate a purge, they will not be able to control its trajectory.

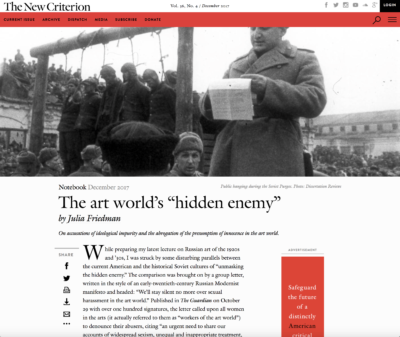

Retouched photograph with Leon Trotsky removed from the side of Lenin’s podium. (image: wikimedia commons)